|

Simply Elia |

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

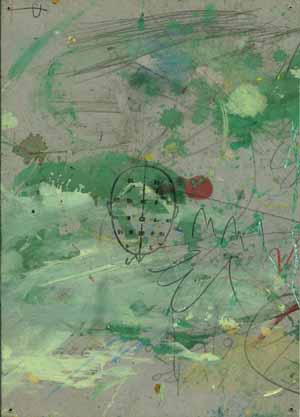

The sudden death of a young artist is always an event

that makes you think. Elia, (born in Adria — Italy as Alessandro Greggio in

1968) died in an accident last August, falling from a window. In the

midst of a career that can barely be called successful, Elia did not

commit suicide. He was too much of a bon vivant to consider such

a possibility. If, as an artist, his satisfactions were limited to his

paintings, he was used to the fact that the Italian art world, in its

self-centered provinciality, was not interested in him. He was an outsider,

well conscious of it, he didn’t mind — or maybe he did, but didn’t show it —

and he accepted his condition and went on painting in the solitude of his

studio, knowing that he was slowly getting somewhere. And he was. Many

a time I told him to put together a portfolio of his abstract

paintings, get a one way ticket to New York and try his luck over there.

He never did, and probably his main obstacle was the fact that he was too

broke to fly over. A happy chap, he knew everyone in Bologna, yet his

deep blue eyes revealed nothing of himself, and it’d take you forever to find

out more about him. Yet he was always eager to show you his paintings, and

quite a successful representative of himself he was: since he left Adria

to study art in Bologna in 1987 he never held a job, and lived off his

paintings and his hands. An amazing craftsman, he would make awesome furniture

and woodwork for whoever asked him to, and some Bolognese shops are

completely decorated by Elia. The saying was "you either go to Ikea, or

to Elia". But all this was just a way of living. He didn’t care

about objects anymore–all he wanted to do was paint. His early works

were strongly influenced by Man Ray, and they closely resemble his Objects

of affection. Even though his style developed into something completely

independent, Elia’s love for Man Ray has been evident throughout his career,

in the way he used painting almost with disrespect. He was very careful about

matter and materials, yet, in his desperate and continuous questioning of

himself throughout the creative process, he would immediately scramble what

he created, starting a drawing with figuration then deforming it into

something else more unclear, more uncertain. Elia knew well that he would die

young, and he would inform you of that when he got to know you well. Once he

wrote to me that he was tired of sticking objects on his canvas (he obviously

couldn’t help it, as he never stopped) and that all he wanted to do was

concentrate on the action of the brush on the canvas, underlying the flatness

of the process. This was hard for him, as found materials had always been the

perfect canvas for him, with all the imperfections that he loved so much. He

was a master of transforming anything new into an antique object–that’s

why everyone loved his furniture so much. But he wanted to stay away from

that and concentrate on what he had inside, on paintings and nothing else. In

order to do that he knew he had to live for the moment. His way of

painting, with the mistakes, the dripping, the furious erasing and the

liberating use of the white, needed the here and now. In the same

letter he told me that he didn’t want to try to get shown anymore, and that

life can’t be planned in advance. This was early in his career and this

decision would further him away from galleries and the art system. Thus his

exhibitions had to happen with little advance notice, in bars as much as in

shops, and sometimes in real galleries. For him the label of the exhibiting

space wasn’t important. He cared about the people who would come and see the

work and get something from it, so he made no social distinction between

anyone. You’d see him in the underground bar drinking with a dodgy guy

one night, at a high-class party a day later, talking to

a wealthy lady. And as the bon vivant he was you’d wonder when he

made his paintings, as you’d always meet him around town. He knew

everyone in Bologna, and Bologna will miss him and his paintings. His mixture

of energy and desperation that, translated into color, became an abstract,

serious search for the perfect painted act. |

||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

|